- Home

- Fernando Rivera

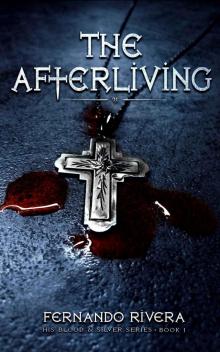

The Afterliving (His Blood & Silver Series Book 1)

The Afterliving (His Blood & Silver Series Book 1) Read online

© 2017 by Fernando Rivera

Fern&Doe Media Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the author, except for brief excerpts in connection with a review or critical article, nor may any part of this book be stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author.

This is a work of fiction. Any similarity between the characters and situations within its pages and places or persons, living or dead, is unintentional and co-incidental.

Cover Design by Despina Panoutsou

Cover Font used by permission of Levente Halmos

Book Design by Douglas Williams

Editing by Caroline Tolley

Copyediting by Amy Knupp, Blue Otter Editing

ISBN: 978-0-9990102-0-4

Vampires, werewolves, God, the Devil, they’re not what you think, and they’re most definitely not make-believe.

After a sleepless night of regretting my decision to come on this trip, the morning sun is the last thing I want to see. I lower the window shade.

A chipper flight attendant approaches our aisle. “Good morning, Mr. and Ms. Stockton. Can I offer you a mimosa or fresh orange juice? We also have tea and espresso.”

Mom’s eyes light up. “So many choices. Espresso, please.”

“And for you?”

“Water. Still,” I reply.

As the woman walks away, Mom looks around the cabin and smiles. You’d never guess she was crying in the bathroom ten minutes ago. “Wow, Manny. First class. Isn’t this fancy?”

I shrug. “It’s okay.”

“Remind me to thank your grandpa for the tickets when we see him.”

“Will do.” I shove my trusty maroon JanSport backpack into the compartment below the television screen. I’ve had it since I was seven. It’s the first thing Mom bought me when we moved to the States from England, and it’s one of the only things I own that isn’t white, navy, or Columbian blue — the colors of my alma mater.

“How long is this flight again?”

“About eleven hours. But I’ve heard time flies right by when you’re in first class. We’ll be in London before you know it.”

“Great.” I force an unenthusiastic smile and pull out my phone, scrolling through unread emails from work.

“Thanks, again, for coming. Your father would have appreciated it.”

“I didn’t come for him. I came for you.”

“Right.” She clears her throat. “Was the university okay with you taking a few days off?”

“They weren’t thrilled about it, but summers are slow, so…”

The top of my screen flashes: New Text Message — The Magician. That’s my therapist, Dr. Kris. She writes: All good?

I respond: Yup. Got my magic and my book. All good.

Dr. Kris replies: Great. Message me if you need to. And remember FORGIVE, FORGET, and have FUN!

I send her an awkward-face emoji and set my phone to airplane mode. Then I stow it in the JanSport and retrieve a worn copy of my favorite book, The Alchemist, along with my five-milligram morning dose of “magic,” otherwise known as Dexolfor. It’s for ADHD.

“What about you? Are you okay?” Mom asks.

“Yeah.” I swallow the capsule with ease and kick off my flip-flops. “I’m salaried, so the time off doesn’t affect my paycheck, thank God.”

“You know that’s not what I mean, Manuel,” she says, frustrated.

We’ve been avoiding this conversation since the day before yesterday, when she first told me Isidore passed away. Isidore Stockton was my father, though it’s been years since I’ve called him that — twenty, to be exact.

“I’m fine, Minerva,” I reply. I search for the nearest flight attendant. “Alcohol is free in first class, right?”

Mom’s green eyes soften. “Manny, talk to me. Please.”

“About what?”

“About your father.”

“Isidore? There isn’t much to talk about.”

“Don’t call him Isidore.”

“Why not? That’s his name.”

“Hey,” she snaps. “Look, I know you two didn’t have an ideal relationship.”

“That’s one way of putting it — ”

“But like it or not, he was your father, and he deserves your respect.”

I stare at her in disbelief. “Have you seriously blocked out the last twenty years of our lives? No phone calls. No letters. No visits. Not one penny from him since we moved away” — not counting these expensive and obligatory plane tickets from my grandfather, Micah. “You can keep denying the facts all you want, but you cannot say he deserves my respect.”

She tightens the seat belt across her lap. “Your father did help us, Manuel.”

“You don’t have to lie for him, Mom. I’m already on the plane,” I reply, fastening my seat belt, as well.

My mother sighs and retrieves a paper from her purse bearing the logo of our San Diego Credit Union. “Happy early birthday” — she hands the bank statement to me — “from your father.”

I scan the form, and my eyes land on the account balance at the bottom of the page. “But there’s…there’s more than five million dollars in here?”

“Shh. Keep your voice down.”

“I don’t understand. He left this to me?”

“Yes and no.” She fidgets with a loose thread in the seam of her leather armrest. “Your father’s been wiring money to us. Every month since we left.”

“Since we left?”

Mom never complained about the abrupt shortage of money that developed after leaving England for the States, and despite our financial circumstances, she never spoke ill of the Stocktons — not even my father. Now I know why.

“So this money’s been growing in some bank account since 1995?” I continue.

“Yes.”

“And you never told me? We could’ve — Oh, my God, Mom. Are you kidding? Why?”

Tears trickle down her cheeks. “Because he loved us, Manny.”

“No. I mean, all this time, why would you keep this a secret?”

“Because I didn’t want you to think we couldn’t make it without him. I wanted you” — she swallows the lump in her throat — “to grow up knowing you could take care of yourself and that you didn’t need his help to survive. I wanted you to be your own man. To make your own choices. That’s all I’ve ever wanted.” My mother lowers her head, ashamed, and dabs the corners of her eyes. “I meant to tell you, honestly. When the time was right.”

That’s one of the last things Isidore told me, too, twenty years ago when we said our good-byes at Gatwick Airport: “You’ll understand. When the time is right.”

“But won’t you miss me?” I remember asking.

“Of course I will. Losing you is like a night without stars,” he said, cupping my cheek with his hand and pressing his forehead against mine. That was his signature I love you gesture. “But this is how it has to be, Emmanuel. Good-bye, my son.”

The nose of the plane rises, and we begin our ascent.

“There’s one more thing,” my mother adds.

“There’s more?”

“Before your father passed, he sent us tickets. To visit him.”

“When?”

“Last month, at the end of May.

And the May before that. Every year since we moved away. I’ve always sent them back.”

“Every year? Jesus, Mom. And you’re telling me all this now?”

“I know. I’m sorry. I never meant to keep this from you. But I also didn’t want your father’s money or his invitations to get your hopes up. His work came first, and he was never going to change.”

She’s referring to Isidore’s obsessive devotion to Stockton Farms, the family business. It’s the reason Mom left him, but to my father’s credit, he always found time for me. That is, before we moved away. In all these years, I’ve never accused my mother of lying to me about why they separated, but every so often, I have suspected an ulterior motive.

“Is that part true? Did you really leave him because of his work?”

“Yes. I’ve never lied about that. Manny, I loved your father with all my heart. He was the man of my dreams, and he was good to me, to us. But he was also difficult. And stubborn. And it wouldn’t have been healthy for you if we stayed.”

“You’re not making any sense.”

“I know. I know.” She wipes her face, smearing the mascara around her eyes. “Just know that your father was not the man you thought he was, okay? And you have every right to blame me for letting you believe otherwise, but I did what I thought was best, at the time. And now that he’s gone, all I’m asking is for you to forgive him… and to forgive me.” She grabs my arm and looks into my eyes, piercing my heart with her guilt. “Please?”

The weight of her regret displaces my anger, and I start to feel sorry for her. What she must have gone through lying to me for so many years… “Okay. I’ll try.”

Mom’s face lights up, and she kisses my forehead. “Thank you, Manny. Thank you.” She notices the black makeup staining her fingers and chuckles. “Oh, my. I must look like a total mess.”

“Well, not a total mess.”

Mom laughs a little louder and takes a compact out of her purse. She covers up her smeared mascara with more foundation.

I look over the bank statement once more, reclining my chair into a half bed. My eyes are fixated on the dollar balance at the bottom of the summary. I can’t believe I’ve been rich for twenty years.

After memorizing the account number, I wedge the folded paper behind the front cover of The Alchemist and turn the page to chapter one.

The only distinguishable shapes are the bright white bars of the digital phone display, 11:59 p.m., which means less than a minute remains until Lucy’s delicate finger will begin to nudge the side of my ribs. We share a bed twice a year — on my birthday, June sixteenth, and her birthday, March twenty-ninth — and her midnight request has become our secret tradition. I’ve tried ignoring her in the past, but she’ll proceed to poke and prod me until I roll over and give in. I know exactly what she wants: food.

When the clock strikes midnight, I smile and wait, but she doesn’t stir. I turn over.

She’s pensive. Frozen. Lost in thought. It’s unnerving.

“Open your eyes,” she finally whispers.

I laugh. “They are open, silly.”

Lucy shakes her head, and her honey-brown eyes tear. “No, they’re not. Open your eyes, Emmanuel. Please.”

I grow annoyed. “Lucy, I’m awake.”

She shakes her head again and pinches the silver crucifix dangling from a chain around her neck. She’s had it ever since I can remember. Lucy turns over and proceeds to cry, muffling her sobs with my pillow.

“Are you okay? Lucy, what’s wrong?”

She won’t answer. Instead, she leaves the bed and runs to the darkest corner of the room. I sit up and call out to her again, but only the shadows answer, creeping forward from Lucy’s hiding place. They spread across the floor and walls, inching closer to my bed, and the room gets darker — colder.

“Where are you, Emmanuel? I can’t see you anymore,” Lucy yells.

“Here. I’m right here.” I extend my hand for her to grab, but all I feel is the cold, thick cloud of darkness.

I jolt awake, startling my mother. “What’s wrong?”

“Nothing. I just forgot where I was,” I lie.

This isn’t the first time I’ve experienced the “shadow dream,” but after this overdue visit to Devil’s Dyke, I’m hoping it can be the last. It comes around twice a year, like clockwork, around the days leading up to June sixteenth and March twenty-ninth. It’s been this way for the last twenty years — “a manifestation of lack of closure,” Dr. Kris suggests.

I readjust my seat and lift the window shade. “What time is it?”

My mother checks her watch. “Well, it’s eleven o’clock. Back home.”

I fish another green tablet out of the JanSport and knock back daily dose number two of Dexolfor.

I haven’t always been medicated. It started after leaving Devil’s Dyke. Our limited finances meant homeschool was no longer an option, and in order to determine what grade I belonged in, I was given a standardized placement test by the San Diego ISD. It wasn’t hard, but it was the first exam I had ever taken without breaks or the comfort of being at home. Needless to say, I didn’t get very far with the questions. The test administrator suggested to my mother I be tested for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. That diagnosis seemed to be all the rage in the States at the time. So I met with a therapist, Dr. Kris, and shortly after, I began an “as needed” regimen of Dexolfor.

The medication took some getting used to, as it made me less active, but I aced my next placement test and skipped an entire school grade. To the added surprise of my teachers, I also adopted a flawless American accent by the end of my first year of public school, which helped me feel like less of an outsider to my peers. I started making more friends, too, bonding with the other kids in class who were also on ADHD meds. Only two of us were treated with Dexolfor, though, me and Andrew Pires. Andrew and I have been best friends ever since. He also works at the university with me, but in the student affairs department. We’re among the countless University of San Diego alumni who never left campus after graduation.

My mother sniffles. I know she’s fighting a new wave of tears. I don’t get it. Yes, she’s mourning a loss, but she’s cried more in the last day than she has in the past twenty years — which would be acceptable if Mom and Isidore were still together. She didn’t even cry the day we left Devil’s Dyke. Has she been bottling up her feelings all this time?

At this rate, I’m surprised she hasn’t fainted from dehydration. “Do you want me to get you some water?”

Mom shakes her head. “No, no, I’ll be fine.” She wipes her eyes and rests her head back, facing away from me.

I pick up The Alchemist once more and continue where I left off, but my mind keeps drifting back to Lucy. Six more hours to go.

As we step off the plane, I pull out my phone and connect to the Gatwick Airport Internet portal.

“Grandpa Micah has Wi-Fi, right? Please tell me he has Wi-Fi.”

Mom shrugs. “I don’t know. I didn’t ask. Does it matter?”

Typical response. She’s the only person I know who still uses a flip phone.

“Unless you want me throwing myself off the roof of the estate from sheer boredom…”

“Quit being so dramatic. I’m sure he has Wi-Fi’s. He has to.”

“It’s Wi-Fi.”

“Whatever. And if he doesn’t have it, you’ll be so busy catching up with him you won’t even notice.”

“Right. You’re funny,” I tease.

When we reach the end of the jet bridge, there’s a yellow sign posted on the wall: Entering a CCTV zone.

I pause. “What’s CCTV?”

“Airport surveillance. Those signs are everywhere. It’s a British thing,” Mom replies. “I want to freshen up before we get to customs. Make sure you have your ID.”

I swing the JanSport around to look

for my passport, and my cell phone connects to the Internet, buzzing with notifications. I stop to check my messages, and someone bumps me from behind. My belongings spill out of the open zipper.

I look up, expecting an apology, but the man responsible is already walking away. “Hey,” I bark, kneeling down to pick up my things.

He ignores me, never turning back.

“Dude, really?” I call out again.

The man disappears into the crowd, but I keep an eye out for him — well, the back of him — from baggage claim to customs. He never reappears. It’s not until Mom and I exit Gatwick Airport that I let the mishap go.

“Oh, my God, Manny, look who it is,” she exclaims. Mom gestures to a tall man in a black suit and tie. “It’s Gabriel. You remember Gabriel.”

“Yeah. Sure.” I recall the back of his head more than his face. Gabriel was one of two Stockton family chauffeurs, assigned specifically to my mother and me. If memory serves me, he wasn’t much of a talker.

“Oh, Gabriel, you’re as handsome as ever,” Mom declares, pinching his cheek as if he were a child. His skin is youthful and unnaturally flawless, radiating in a healthy glow. Hints of salt-and-pepper hair stick out from beneath his chauffeur’s cap, though he doesn’t look a day over thirty-five. He must be somewhere in his forties, at least.

Gabriel nods, and his face blushes a bright pink. “Ms. Stockton, you’re too kind.”

“Gabriel, please. I’m only stating the obvious. And when have I ever let you call me Miss anything? It’s Minnie. And you remember Emmanuel.”

“How could I forget?” Gabriel extends his hand to shake mine.

“Nice to see you again, Ga” — his crushing grip surprises me — “briel. And you can call me Manny.”

“That’s right. He goes by Manny now,” Mom says.

Gabriel smiles, and his ocean-blue eyes sparkle. “Of course.” Then he motions to a black car parked along the curb: a Rolls Royce Phantom with mirror-tinted windows. “Shall we?” He reaches for our suitcases.

“That’s cool. I got it,” I insist.

“No, honey, you don’t have to — ”

The Afterliving (His Blood & Silver Series Book 1)

The Afterliving (His Blood & Silver Series Book 1)